Botticini and Eckstein's Stupid Book [Review]

Cremieux is a blockhead

The field of academic Jewish studies has a relatively wide popular audience. Jews are bookish and self absorbed, certainly at least as much as is typical, and also Jews are quite interesting to other people too. Mostly this is a good thing: it acts as a restraint on academics pursuing pointless avenues of inquiry that the world is justly indifferent to in pursuit of grant moneys controlled by malignant bolsheviks. However, it also has its downside. Jewish studies has more than its fair share of slop books, written by people who are genuinely incompetent to discuss the topic and shamelessly misuse evidence to write speculative fiction. Here’s a review, (in)famous in the field, showing just how bad it can get. Now on to our topic, The Chosen Few by Eckstein and Botticini.

Jews are smart and successful. This is very obvious, and when people try to deboonk it, they just beclown themselves. People naturally want to know how come Jews are so smart and successful. Eckstein and Botticini’s theory goes like this:

In the late second-temple period, and through the classical Rabbinic era, Judaism transformed into a religion requiring textual study, with the result that only those willing to bear the costs of education remained. The Jewish population shrank, but became more intelligent/bookish.

This small, smart population was then perfectly positioned to flourish in urban professions after the rise of the Abbasid empire gave them a reasonable degree of freedom and a large urban economy in which to employ their literacy. 800-1200 under the Muslims was the ‘golden age of Jewry’.

Jews in this period also migrated to Europe to ‘reap returns on their investment in literacy and education’.

The most fundamental problem with this theory is as follows. World Jewry can be divided into 3 populations: Ashkenazim, Sephardim and the rest. Ashkenazim need no introduction, nor is it necessary to demonstrate their high performance across a wide range of cognitively-demanding fields. Sephardim are the Jews of Spain who, after the expulsion decree of 1492, spread across the Ottoman empire, quickly becoming the religious and economic elite of Jewish communities across the region, generally acting like jerks and forcing the natives to change their liturgical and halachic practice. Their intelligence is not as impressive as the Ashkenazim; it’s probably about the same as the English. But the English have done some pretty cool stuff, and there are many eminent Sephardi Jews too. The last category are the Arabic-speaking Jews of the Muslim world that the Sephardim have been bossing around for the last 500 years. There has been substantial intermingling over that period, though there are still large populations that are mostly one or the other. The Israeli neologism ‘Mizrahi’, meaning ‘Eastern’, is used to describe sometimes both groups and sometimes only the non-Sephardim, though Morocco is to the West of Poland last time I checked. I am going to use the term Musta’arabi because it’s cool, though technically it doesn’t apply to Iraqis and Persians.

Now, among Musta’arabim there is a range of abilities, as there is in any group, and they have their wise men and sages. However, if all Jews were Musta’arabim, they would be no more notable in world history than Middle Eastern Christians, and maybe less so. What we are looking for, therefore, is a theory of what made Ashkenazi and, to a lesser extent, Sephardi Jews special. For the first, we actually have a good explanation already, though nothing in particular for the second. However, Eckstein and Botticini’s theory is precisely not that: it’s an explanation of why all Jews became smart and successful. Indeed, since the Sephardi and Ashkenazi groups, as we shall see, are overwhelmingly descendants of those who branched off before the period 800-1200 when, according to E&B, Jews in the Abbasid empire became a historically unique people, it’s essentially a theory of what makes all the Jews apart from Ashkenazim and Sephardim special. In other words, the thing they are explaining isn’t actually true in the first place.

That’s a fairly serious problem with the book right off the bat. The other main problem is that, as we shall see, almost every page contains hallucinations, gross misunderstandings, and major factual mistakes. It’s an appalling book that is positively perverse in the way it simply ignores the scholarship of the last 40 years to draw ambitious conclusions from meagre, or completely fictional data. However, and this is why we’re here, Cremieux has repeatedly pimped this ‘brilliant’ book. The reason I think this is somewhat important is that none of us have the time and aptitude to cultivate informed opinions on everything that interests us from primary data. We therefore have to cultivate a bank of authorities that we can trust for different topics. Cremieux seems to be a good candidate for that. He’s data-driven, stylistically unpretentious and an advocate for hereditarian neoliberalism, which is where people who are smart and aren’t deranged tend to converge after a while. However, there is no avoiding the following conclusions:

Anyone who has even the slightest familiarity with Jewish studies cannot fail to notice how bad this book is, and therefore it is clear that Cremieux forms strong views on topics without doing even elementary background reading.

Even without knowing anything about Jewish studies, there are certain features of this book that should set off your bullshit detector if it functions at all, and therefore Cremieux does not have a functioning bullshit detector.

The specific flaw of this book is that it, over and over again, builds a whole network of speculation on extremely flimsy data, ignoring easily available evidence that contradicts this theory, and, if Cremieux thinks this is a brilliant book, that indicates something very bad about his entire way of generating opinions from data.1

We shall now go about demonstrating how bad this book is, but, before that, I’ll say that any reasonable person should respond to this by downgrading Cremieux as an epistemic authority, and failure to do so can only be ascribed to Gell-Mann amnesia.

Eckstein and Botticini rely on made-up population figures

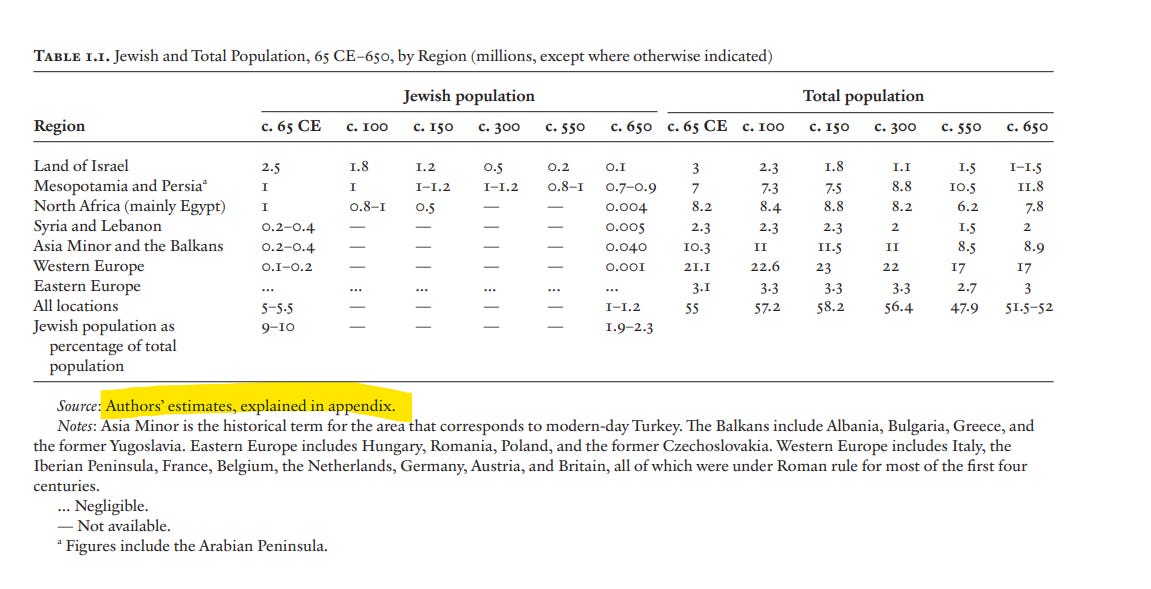

On page 1, B&E ask the question ‘Why did the Jewish population shrink from 5– 5.5 million at the time of Jesus to 1– 1.2 million in the days of Muhammad?’. This is an absolutely crucial lynchpin of their entire theory, since, according to them, the explanation is that Jews who could not handle the Rabbinic literacy requirements left the faith. But where do these figures come from? They explain:

Again, if you know bullshit, you know this is bullshit, but if you know anything about the field, it gets worse. B&E try to position themselves as taking a reasonable middle ground between Salo Baron ‘one of the most eminent scholars of Jewish history’ and Broshi, Hamel and Schwartz. But if you just google for five minutes, you find that:

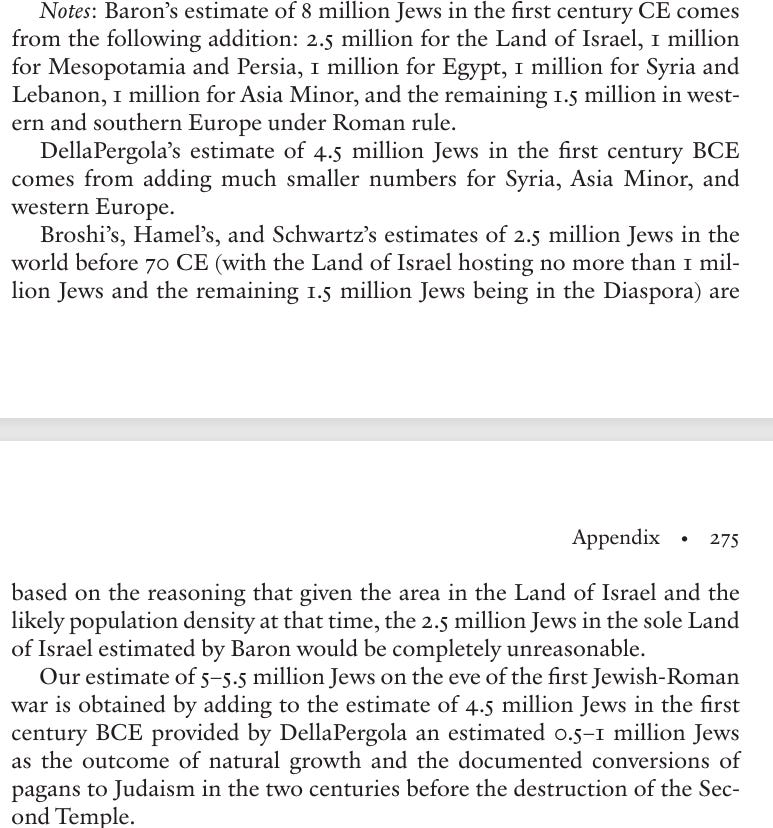

So the 8 million figure is just garbage with no value whatsoever, and either B&E know this and are deceiving the reader, or they are completely incompetent to be writing this book. They are in actuality arguing for the upper-bound figure (to which they just arbitrarily add another million), advocated by someone who isn’t an ancient historian, because they agree with it. Is there some more?

Hmm, sounds interesting, let’s check out the Appendix:

So they note that the population estimates they are using are ‘completely unreasonable’ and use them anyway because … because … because … LITERALLY NO ARGUMENT WHATSOEVER.

It is important to emphasise that this is not a small and unimportant part of the book. The entire first chapter goes through methodically establishing that Jewish population collapsed over this period, reviewing each area of Jewish settlement in turn. In each case they do this by juxtaposing completely fictional, obviously wrong population figures for the beginning of the period, with more reasonable (though not, in fact, especially well evidenced) figures for the end. Naturally, this transition from myth to reality ‘demonstrates’ population collapse across the board.

However, it’s worse even than that because, in Palestine, the home of the Rabbinic movement on which their theory hinges, the actual story is something close to the opposite of what they portray.2 After the Bar Kokhba revolt, te district of Judea was substantially depopulated and archaeological evidence of Judaism disappears. Roman Palestine looks just like Roman anywhere else, except with fewer people in large parts of it. Were it not for literary sources, we would have no reason to think Judaism had survived at all. However, these literary sources, if read with thought, only attest to the existence of small pockets of observant Jews in the Galilee region. B&E correctly point out that it is not plausible to suggest that all the Jews died in the three revolts (though a population decline of a quarter is not at all implausible), but it is not necessary to posit that because there is a very simple explanation: they gave up, just like the Gauls. Whether or not the population who lived in the Roman cities of the Palestine still considered themselves Judeans, or what that meant, is an interesting question, and one we have few tools to answer, but those loyal to any version of the old faith were a small minority.

What then happened is that the Jewish population grew, with the exception of the mid-4th century crisis, an event that seems to have had mostly economic/natural causes and to be scarcely related, if at all, to the conversion of the empire to Christianity. The evidence for this growth is two-fold. First, the architectural record shows an increase in the number of Jewish monumental buildings, primarily synagogues, up until the last Byzantine-Sassanid war, and that existing buildings were being upgraded and expanded. The second is that two bodies of literature explode during this period, specifically the midrashic corpuses, and classical Jewish liturgical poetry known as piyyut. Earlier historians missed this because (a) they assumed that the hair-raising laws against Judaism promulgated in Byzantine codes represented the reality on the ground, and (b) they interpreted the end of productive legal Jewish literature as indicative of a general cultural collapse. In reality, while the project of the Talmud Yerushalmi was certainly abandoned half way through, the decision not to continue after recovering from the mid 4th century crisis seems to have reflected a conservative halachic sensibility and a change of focus, as well as probably the loss of some specific intellectual human capital to Bavel, rather than general decline.

To sum up, B&E base their thesis on population figures that are fictional and the opposite of what actually happened. Their claim that the Jewish population up-skilled itself over 100s of years by gradually shedding those who couldn’t cope with the Rabbinic requirement for literacy doesn’t get off the ground.

Eckstein and Botticini consistently rely on old and debunked scholarship

This is the primary sources section of the bibliography:

So, basically, some stuff about medieval Italian Jewry that Botticini could take a train to look at, but nothing relevant to most of the book. To be clear, that is not a problem. Books that synthesise large amounts of existing research to build up a coherent picture are a very legitimate and necessary part of intellectual progress. However, this requires you to actually have read the relevant secondary literature. Despite their claim to have spent years ‘sifting through an immense body of literature, meeting with scholars and experts on Judaism and Jewish history’, this is precisely what B&E have not done. Or ,alternatively, they did do it but chose to repress what they found because it would have meant throwing their thesis in the bin.

What B&E do throughout the book is cite alleged facts from 50-year old or more history books, and ignore all of recent, and not even especially recent, scholarship. There are fields where this would be less disastrous. In Virgil studies, for example, most of the real work there is to do was done long ago, and contemporary academia is substantially composed of wankers ‘interrogating’ the text to find justifications for communism or being a weirdo pervert. However, Jewish studies is not like that. Until the 1970s, it was stuck in what Collingwood describes as ‘Scissors and Paste History’. Recent advances have mostly consisted of applying basic standards of critical analysis long routine in other historical domains to the source material, powered by a steady flow of OTDs and Modern Orthodox eggheads with solid talmudic bekius looking to turn that into a steady income.3 Relying on histories written before the 1980s is basically like using a medieval chronicle as your textbook (note that we saw that this is literally what frequently cited population estimates were based on).

You can more or less take any footnote from the book and see this in action, so I’ll confine myself to a few examples that took my eye.

As they do in many cases, B&E stick one more modern work in their list of sources to maintain some baseline credibility (though it’s still 22 years before the publication of the book). But they are obviously cheating. Louis Jacobs was a heterodox Rabbi and theologian, not a historian, and he certainly wasn’t doing original research at age 70 when he wrote the cited article. On top of that, R. Jacobs was a paradigmatic example of the ‘naïve-critical’ mode of Rabbinic studies pioneered by Heinrich Graetz and exemplified by Louis Ginzberg and Louis Finkelstein.

The hallmarks of this approach are twofold. First, the historian reads halachic texts (the only bountiful source of information we have about late-antique Jewry), against the grain, reading ‘behind’ the legal and hermeneutic debate to discover the ideological agendas or material factors supposedly driving different halachic opinions. The problem with this approach was ably explained by Christine Hayes in a quite readable book published in 1997 that B&E could have consulted if interested:

The second hallmark of this approach is the ‘kernel’ approach to Rabbinic stories. This entails taking narrative sections from the Talmud and other rabbinic texts and removing miraculous or obviously legendary material, thus leaving the reliable historical data underneath. However, this makes no sense. If the transmitters and recorders of these stories could add or invent details, then there is no reason to think they restricted themselves to obviously impossible ones.

By putting these two techniques together, great webs of fiction were weaved in histories of the Jews. For example, the House of Hillel represented middle-class interests vs. the House of Shammai’s support for the upper class. How do we know this? Well, the house of Hillel were a bit more lenient in the requirements for making eruvim. These fictions were then cited by new fiction weavers to build up increasingly sophisticated narratives until modern historians pointed out it was based on nothing. [Actually, Orthodox polemicists, back before the total triumph of obscurantism and philistinism in our religion, did a pretty good job of debunking this stuff, but the academy paid little attention]. Often the ‘findings’ of these scholars are so wrong as to beggar belief. For example, Finkelstein revealed the famous Dayyenu poem sung around the world at Seder night as a piece of pro-Ptolemaic propaganda authored by the High Priest Jason, and this was a staple part of the clever Jew’s repertoire for finding something to say during the meal for decades. The only problem was that he misdated the song by about one thousand years.

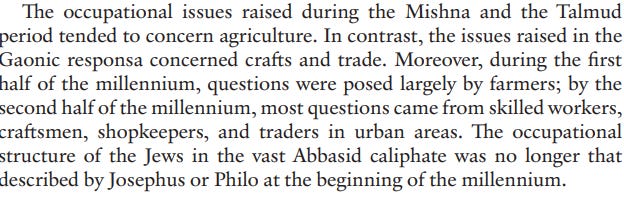

To return to our case, the idea that the Babylonian amoraim initiated an exodus from agriculture to the professions is a typical, if relatively benign, example of this kind of fiction-weaving, and B&E would know this perfectly well if they had any interest in accurately understanding the period they want to explain. Another example:

Again, this is cheating, if a bit less so. Moshe Gil was a very important pioneering historian of Middle Eastern Jewry. The work cited was first published in 1997, when he was 76, and synthesised much of what he had written over the course of his career. Already by then, his approach was somewhat out of date. However, more to the point, while the cited pages do describe the ‘massacres, epidemics and famines’ in this period, they do not substantiate B&E’s claim of the total collapse of Islamic urban civilization. This is an important point in the book. B&E are dimly aware that fact that Musta’arabi Jews haven’t done anything interesting for the last 800 years while Ashkenazim and Sephardim have been running around changing the world. Their explanation is the Mongol Shock turned the Middle East into a post-apocalyptic wasteland where nothing could be achieved. The Ottoman Empire is a fiction of your imagination. I am not mischaracterising:

It almost goes without saying that this is an insane exaggeration. It’s an insane exaggeration that comes from uncritically reproducing medieval chronicles, which is what historians did before World War 2. And it is these historians upon whom B&E rely for their funhouse of mirrors Jewish history. By now you’ve probably got the gist, so you can figure out what’s going on in this example by yourself:

Eckstein and Botticini completely botch the origins of Ashkenazi and Sephardi Jewry

The reticence in this footnote is funny because nowhere else do B&E demonstrate concern that the population figures they use are fictional. However, it may be that it is deliberate. I think the vast majority of people who are not familiar with the topic and (woe be to them) rely on B&E as their source of background information will conclude that Sephardi Jews were the descendants of Jews who settled in Spain following the Muslim invasions. But this isn’t true. Spain already had a large Jewish community under the Visigoth kings with roots going back many hundreds of years. The Visigoths (a dynasty who arrived in Spain after the Jews) had subjected them to increasingly intense persecution following their conversion from Arianism to Catholicism/Orthodoxy. As a result, the Jews welcomed the new Muslim conquerors and played some role in helping them conquer the country (though the extent to which this was militarily important is probably exaggerated in later hostile Christian sources). It was precisely because they were a loyal native population in a country where Muslims were initially a tiny minority that Spanish Jews enjoyed a unique degree of legal privilege and cultural prestige in Al Andalus.

It is probably true that more Jews eventually travelled from the Middle East and North Africa to be part of the prosperous Sephardi community, but Sephardim were mostly the descendants of those who were there before. This is important for various reasons. First, we know almost nothing at all about the religious life and practice of Spanish Jewry before the Muslim invasion, with our main sources being anti-Jewish Visigoth laws and polemic. However, it is almost certainly the case that the rabbinization of far-flung and isolated Spanish Jewry started later and proceeded more slowly than among Middle Eastern Jewry, before accelerating after the Islamic conquest. This is obviously a major problem for a theory that locates the cause of Jewish success in that process of rabbinization during the period before the rise of Islam. Secondly, since Sephardi Jewry was far more accomplished than Abbasid Jewry both during this period, and for all of history until the present day, it would appear that their specific experience as subjects of a persecuting Christian regime is more important as a determinant of Jewish accomplishment than the mechanisms pointed to by B&E. They seem to be aware that this is a massive problem for their thesis, and deal with it by just pretending that the Sephardi Jews were an offshoot of Middle Eastern Jewry.

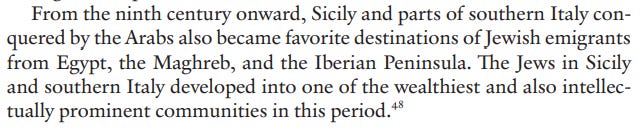

E&B’s treatment of Ashkenazi Jewry is similarly evasive. Liturgical historians noticed long ago that it looks like they came from Palestine, or a community with Palestinian customs, and genetic data shows they are about half Italian. It was once thought that maybe they were POWs from the Bar Kochba revolt; subsequent research shows it was a lot later than that, but still not late enough for B&E’s thesis. The Ashkenazi founder population was already in Italy and mixed with a local population by conversion/intermarriage before the ‘Jewish Golden Age’ of the Abbasid empire. This is how B&E cope with that:

It is absolutely not true that the Jews of Sicily and southern Italy became one of the wealthiest and prominent communities, but the point here is to blow smoke and make it look like, since we know Ashkenazim came from Italy, they are descendants of Jews from the Abbasid empire looking for investment opportunities. Hence we get:

One ‘on the one hand’ is not like the other, since the first is documented and the second is just them making stuff up. But maybe if you’re vague enough people won’t notice and just assume Ashkenazi origins fit their theory. Cremieux sure did!

Eckstein and Botticini are very confused about what urbanisation is

Manhattan is urban; downtown Chicago is also urban. That does not mean the denizens of these two places have a shared strategy for cultivating and leveraging human capital. Or put it this way. The following are two examples of urbanisation. (1) In the 18th and 19th centuries, the landed gentry of England bought houses in London to spend the ‘season’ there. Over time, they more and more came to spend the bulk of their time in London, with their country estates gradually morphing into holiday homes. (2) Over roughly the same period, agricultural labourers saw a collapse of their real income driven by productivity gains and population growth, and therefore went to the cities to find work in factories. These processes happened in the same society, and as part of one large process of economic development, but they are really obviously not the same thing. Anyone who mixed them up would obviously be talking drivel. So naturally that’s what B&E do.

You think I’m exaggerating, but, again, no:

Tanning is a skilled profession, but it was definitely not an elite one. It’s about the least elite one you can imagine, involving daily interaction with foul smells, and, typically, human or dog excrement. In many cultures, including rabbinic Judaism, tanners were considered social outcasts. The world is a big place and, no doubt, some a son of a tanner somewhere has become a royal physician, but with no more regularity than the son of a farmer.

The important point here is that, while Musta’arabi Jews have been overwhelmingly urban going back a long time, their urbanity consisted mostly of low-level artisanry and trades. It goes without saying that the world needs these people as much as, if not more than, other social classes, but merely being urban in this sense is in no respect whatsoever a preparatory for entrance to the elite, or for attaining the kind of prominence in global human culture that Sephardi and Ashkenazi Jews have attained. It should also be obvious that literacy is not a pre-requisite for tanning, and tanners are not known for being literate. This brings us finally to the meat.

Eckstein and Botticini completely misunderstand Rabbinic Judaism

So far, Cremieux might be able to wriggle out of this by saying ‘though the book is poorly argued, has mistakes and hallucinations on practically every page, and is deliberately evasive about key points, the basic thesis still has some merit’. That’s a bit different from saying the book is brilliant and then just repeating all the wrong things it says. However, it’s moot because, as we’ll see, E&B’s misunderstanding means their whole theory is not only a bad mismatch for reality, it’s not even plausible hypothetically. Before we get to that, though, it’s important to make clear just how much E&B don’t have any clue what they are on about:

It’s true that the Tannaim did not ‘devote time and attention to philosophical discussions’, however, they absolutely did devote time and attention to legal questions with no practical application to their era. How easy it is to establish this point? Just as one ‘volume’ of the Mishnah is devoted to agricultural laws, so one volume is also devoted to the sacrificial cult in the temple, which had not existed for about 150 years at the time of the redaction of the Mishnah. However, that rather undersells matters. Half a dozen tractates in the other six ‘volumes’ of the Mishnah also deal mostly or entirely with temple ritual, bringing the total to around 1/4 of the whole Mishnah.4 If we include all the other things that had no practical application in this era, it’s a solid half. From the off, therefore, the prominence of agricultural laws in the Mishnah tells us nothing about their importance in the daily lives of Jews.

It’s worse than that, though, because if you have flicked through the ‘volume’ of Zeraim, you would know that one tractate has nothing to do with agriculture, two concern topics which were non-applicable in the Rabbinic era, and three principally concern not farmers, but consumers of food, which people in towns also eat. In reality, therefore, it’s less than a 12th of the Mishnah that concerns agriculture per se. Then B&E say this:

This is straightforwardly not comparing like with like. The Mishnah is an imagined constitution for a quasi-utopian Jewish polity; Geonic responsa are questions asked by people seeking guidance, sometimes, it is true, in explicating a difficult talmudic passage, but more often seeking practical guidance. There is a very simple reason why few of these questions concern the agricultural laws. Palestinian Jews had their own rabbinical establishment, so essentially all questions asked to the Babylonian Geonim came from outside the Land of Israel where the agricultural laws are not operative.5 They would not ask how to take tithes in a given circumstance, regardless of their occupation, because they did not take tithes.

The big joke here is that there are actually ways to use rabbinic literature to track the changing socio-economic status of Jewry, but B&E have no way of accessing this because they are less well informed than one would expect from someone who had taken a one semester Introduction to Judaism course at a reputable university. The first of these is to look for unexpected leniencies in legal rulings. If you find a cluster of these in a particular area then that indicates this was a live issue because, though Rabbis discussed issues with a wide range of contemporary saliency, the obvious motive for leniency would be to lessen the halachic burdens on the existing Jewish community. In fact, in the early era of the Amoraim, we do find multiple cases of odd leniencies being granted for exemption from agricultural laws, whereas in the latter eras the same phenomenon is found elsewhere (most notably usury). The second is by looking at civil law. Thousands of different cases are discussed and analysed in Jewish literature. ‘What is the rule if you hire a donkey to carry dates and it carries figs and breaks its leg?’. ‘What is the rule if you pay someone to store your wine in his cellar and the barrel breaks?’ That sort of stuff. Though these examples are not necessarily practical per se. they are supposed to be relevant in the sense of making general principles easy to conceptualise. If we can trace how the content of civil law discussion changes over time - and all the more so the content of questions asked to the Geonim about how to rule in specific disputes - we can come up with something plausible about what kind of occupations halachically observant Jews were in over different periods. This is thus one of the few things E&B say in the book that isn’t just flat wrong, but it’s by accident.6

We also have to say something about E&B’s use of rabbinic source material. This has widely been critiqued as naïve. However, naïve would genuinely be a major step up. Take this:

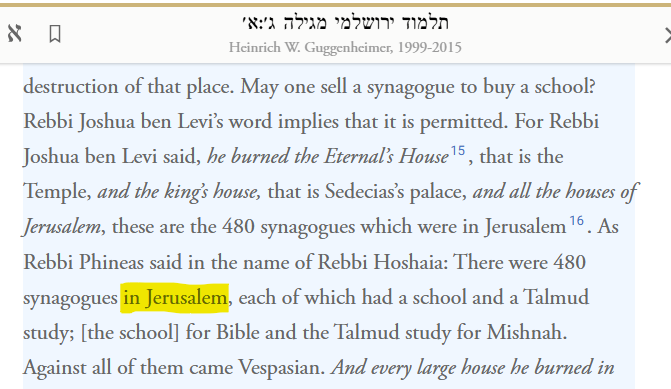

Any reader will naturally assume that the second quote describes the period 200-650. However, what if you weren’t a complete clown? What if you just spent a few minutes checking it up?

Leave aside whether בית ספר means ‘elementary school’; leave aside that they got the name wrong. This is a claim - an obviously legendary one - about Jerusalem before the destruction of the temple; it is not evidence for the reality after purported rabbinic reforms 100s of years later. Is there a way of taking the original quote and turning it into the one in the book without malicious omission and re-arrangement? I can’t see one.

There are dozens of citations and assertions that are just as bad, and if anyone jerks me around about it I’ll list them. Just one more.

However, for the time being, I hope we’ve established that B&E are lost in a topic they don’t know anything about and don’t even adhere to basic standards of honesty in their ignorance. So, with that out the way, let’s get to the key question. E&B claim that the Rabbinic norm of promoting literacy was unique in the ancient world and made the Jews a unique people. This is actually 2 claims (1) the Rabbis set out to promote universal literacy (2) they broadly succeeded. A lot of criticism has been focussed on (2) since E&B’s evidence for this is … nothing basically. However, it’s not even necessary to get into the weeds of that because (1) isn’t true in the first place.

Was Rabbinic Judaism pro-literacy?

There is no word in Rabbinic Hebrew that means ‘read’. Sometimes we find words meaning ‘gaze’ or ‘ponder’ used to denote reading, but the word that is generally translated it as ‘to read’ is לקרות. This is a development of the biblical לקרוא, which means ‘to call’ and is sometimes used in the form ‘to call in a book’ i.e. to read it out loud. However, לקרות clearly does not mean ‘to read’, but rather ‘to recite’. We know this because the word is frequently used to describe reciting a text from memory, or even repeating what someone else has recited. However, even when the word refers to reciting a passage using a written text, it does not refer to reading in the ordinary sense of the term. Hebrew at the time had only consonants and no marks to indicate vowels. Modern Hebrew is also like this and it’s mostly readable to those who speak it fluently, however the biblical text (a) often lacks orthographic vowel markers ו and י, that are frequently necessary to make Hebrew legible and (b) contains numerous examples of words that could be easily read multiple ways (e.g. active or passive inflections of a verb) and can only be read correctly based on tradition. In addition to that, Jewish tradition in many hundreds of occasions reads a word in a way that cannot be reconciled with the consonantal text, and this could only be known by consulting a sage. Finally, correct recitation of a text means including pauses and melismas at the correct places, which are simply not a property of the text at all, and must be remembered orally. Today, all this information is included in printed copies of the Hebrew Bible through an elaborate system of diacritics, but it is not in the scrolls used for ritual recitation and, in the rabbinic period, the diacritical system did not yet exist.

In modern Jewish-English, the word used for this type of ritual recitation is the Yiddish, lein. As any observant Jew can tell you, reading and leining are two quite different things. Almost all Jews today can read (outside of Israel, where literacy is declining), but only a small minority can lein. On the other side of the coin, one can be a competent leiner while a mediocre or worse reader. The schul ba’al koreh is unlikely to be the most bookish member of the congregation. So, while obviously not completely unrelated, reading and leining should not be conflated, and this conflation is the central pillar of B&E’s whole thesis.

Literacy, certainly the kind of literacy that is economically valuable, entails being able to approach an unfamiliar text and, by scanning the marks on the page, decode the meaning intended to be transmitted by the one who composed the text (I apologise to all the philosophy goons for this naïve formulation). This kind of reading was not unknown to the Rabbis, it’s just that they didn’t like it. Gaining information through private reading of non-canonical texts was considered suspect and foreign, even if the information itself was completely kosher. Halachic ‘texts’ were not supposed to be read, but rather memorised from someone who had memorised them himself. ‘Reading’ was a ritual performance; the only legitimate way of transmitting information way orally. The talmud also prohibits writing down liturgical texts, and prayer consisted almost entirely either of (a) reciting a limited set of well-known texts and blessings, often in unison or by antiphony or (b) listening to a cantor (or sometimes a choir) and answering either amen, or other well known refrains such as haleluya or the kedusha verses. The strong Rabbinic taboos on writing down the Oral Torah or prayers only started breaking down well into the Geonic era, long after B&E claim that Jews were cashing in on all the literacy rabbinic educational reforms had endowed them with over the preceding period.

The funny thing is that, while B&E claim that becoming Christian was a way that Jews could maintain their Hebraic monotheistic beliefs without having to learn to read, if there’s a candidate for an ancient religion that actually did make a big deal of literacy, it’s Christianity. Within one generation of Jesus’s execution, we already find that the leaders of Christianity are writing each other long letters in Greek with complex argumentation and multiple literary allusions. This body of written literature, called by them the New Testament, on its own dwarfs anything produced by Jews until the 9th century (since the Talmud wasn’t written down). In the centuries after that, the way to become a top-status Christian was to spend a lot of time reading the Bible and Greek philosophy and then write long texts explaining why other top-status Christians were heretics because of [big Greek word]. It is unfair, of course, to compare Jews and Christians after 312 when the latter had the power of the empire behind them, but there is nothing like a Jewish Tertullian, a Jewish Origen, or even a Jewish minor-ante-Nicene-Church-Father-who-you-haven’t-heard-of-and-are-frantically-googling [‘Lactantius’: that can’t be a real name]. In earlier eras, Jews had done that, but in the Rabbinic era they didn’t; they were doing other stuff.

It may well be objected that the Christian ideal of the scholar-saint was never intended for the general masses, and that’s fair enough, but at least it was an ideal. Rabbinic Judaism not only didn’t put reading on a status-pedestal, it didn’t even really put leining on a status pedestal. B&E make much of Rabbinic imprecations against the unlearned amei ha’aretz, reasonably inferring that this generated an incentive for them to leave for a less snobbish religion, but the amei ha’aretz are described as lax in rabbinically-mandated observance and knowledge of the oral law. Not a single source identifies inability to lein as characteristic of an am ha’aretz. Indeed, there’s no real evidence that the Rabbis sought to promote general standards of proficiency in leining, or that they thought this to be part of their role. Already in the Tosefta, the question is raised of what to do when only one person in a synagogue knows how to lein [the answer is he recites the seven required readings himself]. Sefer Hilukim, written sometime between the 7th and 10th century, attests to the existence of the institution of the ba’al koreh, whose job it is to perform the recitation while the people called up to read from the Torah stand next to him trying to look cool. During the Geonic era, there were two separate institutions of learning in Tiberias, one for the study of the oral law (the yeshiva), and another for leining, from which we get the Masoretic system that Jews theoretically use today. The institutions were separate to the extent that the latter saw no problem in having Karaites study and even teach there.

So, to sum up, the problem with B&E’s model is that every aspect of it was wrong. Rabbinical Judaism did not promote literacy; Jews were not highly literate; the Jewish population did not decline progressively over the talmudic period and therefore did not decline by shedding illiterates. Their book is unbelievable garbage and, to return to the main point, Cremieux is a braggart with poor judgment whom you can trust to make grave errors on any topic outside his personal competence because he has no clue how to assess arguments or weigh information, and doesn’t care to develop one. For the final part today, we’re going to show what a more plausible model explaining Jewish uniqueness looks like.