Gaza and Chechnya

More obvious stuff for slow learners

If you’re in the thinking game, it’s important to keep some sort of record of the arguments you have made, and then check back to see whether (a) a clear prediction or inference you made has been demonstrated to be false or (b) you are now arguing something contradictory to what you formerly argued, but still maintaining the same conclusion. Dorks call this ‘practicing good epistemic habits’. I don’t do that, but I do have a good memory, and sometimes a light bulb goes off.

The one I’m going to talk about here is from back when I was a guy commenting on Steve Sailer’s blog. Are you an interminable sad-act? Do you remember the handle on Unz Review always either quoting Moldbug or simping for Israel? Me! This was many moons ago in the before days when ‘Stormfag’ was still a broadly intelligible insult, and I was arguing with a proper Stormfag about Israel. He pointed out that Russia had found a way to make it work even with Chechens, who are Muslims and insane mountain people, so, he reasoned, Israel could make it work with the Palestinians if they wanted to, but they don’t want to, because they just want more land. I argued back that Russia had used far more force against Chechens than Israel had used against Palestinians (true), and that if Israel would be allowed to use the same degree of force, the problem would be solved in a similar fashion (to be determined). Then it was determined.

Background

The Second Chechen War began in the autumn of 1999, prompted by an invasion launched by Islamist militias into neighbouring Dagestan, as well as a series of terrorist attacks in Russian cities that killed more than 300 people. Before the Russian invasion, Chechnya had been a de facto independent state, having declared independence during the collapse of the Soviet Union, and successfully resisted Russian attempts to reassert control in the First Chechen War of 1994-1996. These attacks were, in a sense, the Russian October 7th, prompting a wave of disgust at unprovoked targeting of civilians by a people who had received their independence and used it, not to pursue peace and prosperity, but rather pursue irredentist goals. Chechen militants responded to the Russian invasion with even more terrorism, including the Stavropol train bombing, the Moscow metro bombing, and most shockingly, the Beslan school massacre.

Presumably, the intention of Chechen terrorism was to demoralise Russian public opinion, so that the Russian state would end its ‘counter-terrorism operation’ in ignominy, as it had in 1996. However, the effect was the opposite. The Russian public were determined that the Russian army would win at any cost, both in terms of Russian army casualties (estimates are between 6,000-14,000) and Chechen civilians (probably 25,000). The final result was that a source of ongoing trouble and instability for the Russian state became an asset. Chechen troops have, since the conclusion of hostilities in 2009, served Russian state interests in putting down rebellions in neighbouring Muslim-majority provinces, waging war in Ukraine and projecting imperial power in Syria, Libya, and Armenia. Chechen troops are generally regarded as among the best that Russia has at its disposal: more fierce, more brave and less generally useless than the brutalised graduates of Russian military training.

Nation and State and the Nation State

However while the Second Chechen War was unquestionably a triumph for the Russians, and the proof-of-concept for Putin’s two decade project of rebuilding Russia from the ashes as a B-tier global power, it was certainly not any kind of victory for Russian nationalism.

In 1991, about one quarter of the Chechen population was ethnically Russian, and among the rest Russian was the language spoken by anyone who wanted to get ahead in life. Islam and whatever rustic click language it is that Chechens speak was for old women and hopeless poor people; indigenous culture was gradually, but inexorably on its way out, to be preserved in some ethnic food and nostalgia, just like Cornwall or Brittany. Over the course of the Chechen wars, however, the ethnic Russian population mostly fled, with the proportion dropping from 25% to 1-2%. The Russian language is also in declining use, especially among the young, with Chechen culture and religion systematically promoted through the education system and local media. De-Russification has proceeded far more quickly and far more thoroughly than in the Ukraine. In addition, the general Russian population has to pay up for all this, with 90% of the local government budget being supplied by federal grants, contributing to stuff like this:

There are two reasons why this is a tolerable situation for the Russian state. The first is that Russia is really big. If Chechens want to have hijabs and bacon substitutes it really doesn’t affect Russians living multiple timezones away. It doesn’t even matter really if the Chechens are all nutty terrorist supporters, as long as they keep it at home. The second is that Russia has a whole ideology to accommodate this. The Russian language distinguishes between russkiye, ethnic Russians who are the core population of the state and rossiyane, Russian citizens. You can be a good rossiyanin without being, or wanting to be, or LARPing as a russkiy. Chechens can have their own patch without in any way being disloyal to the larger ‘Russian’ project. Apparently, this linguistic distinction was concocted in the early 1990s, though it has roots in the era of Peter the Great. Regardless, it works pretty well, much better than the ongoing fiasco of Putin’s later pivot to pan-slavism and brooding over the Kievan Rus. Smarter Putin loyalists like Eli from Russia still understand that the multinational empire card is their strongest one.

The arrangement the Russian empire makes with its geographically concentrated minorities can be understood as a sort of trade. In exchange for loyalty and renouncing aspirations to full independence, these minor nationalities get to be part of something bigger and cooler than they could ever aspire to, and also benefit from being part of a large free trade zone. Because Russia is so big and populous, it can accommodate a large number of these minority groups existing with substantial autonomy, just so long as russkiye TFR is high enough to maintain an overwhelming demographic super-majority, which it isn’t, so probably this is all going to implode in due course. What we’re really here to talk about though is Israel, so let’s start applying lessons.

In Israeli and pro-Israeli discourse, the Palestinians are conceptualised fundamentally as foreign antagonists. This makes a certain degree of sense, because they are foreign and antagonistic, but it misses something important. The State of Israel has exercised sovereignty between the river and the sea now for 58 years. This is longer than the period that the West Bank and Gaza were ruled over by Jordan and Egypt (19 years) or the British mandate (28 years). The previous period of Ottoman rule (1840-1918), was only a few decades longer. By ordinary standards we use in thinking about any historical era, the Palestinians of the West Bank, at least, are the subjects of the Israeli state. The fact that they exist in a state of permanent hostile opposition, active rebellion only prevented by the constant and escalating use of force, shows that Zionism is an objective failure at the task it has been set by history, namely providing a political order that integrates the population of human beings that live within its territory.

This is the problem, and problems invite solutions. The most farcically stupid solution to this problem is called the One State Solution, in which Israel abandons its insistence on being a Jewish state with a Jewish majority and gives all people under its control citizenship on a roughly equal basis. The wrinkle is that creating a stable political order is hard, and creating a violence-ridden basketcase is easy. State institutions don’t just fall from the sky; even if it gets a new name, the new state will be, at the beginning, still Israel, just with more people in it. These people don’t get along at all. What will the state have at its disposal to settle their disputes, beyond what it does right now?

Let’s look at it a different way. A state is a way of solving thousands of overlapping prisoners’ dilemmas at once. Everyone agrees that they will let the state tax them, settle their disputes, pursue their feuds, and issue commands in order to live in a state of peace that for most is preferable to the breakdown of order. But no substantial number of people have ever actually made this decision in those terms. The most powerful and effective prop for state power is habit, but that is precisely what those establishing a new political order don’t have at their disposal. Another good prop is swift and vindictive violence, but this only works against minorities when you have the majority already onside, and even then less well than you might think.

What you need, rather, is reasons. These reasons don’t need to be good as measured against a coherence or correspondence model of truth, but they do need to be psychologically powerful. For all but a minority of the neurodivergent, when we look for reasons to be loyal to a state, we are really talking about reasons to think that the state in question is awesome. People want to identify with something great, not something lame. In the case of Israel, obviously, there’s not much mileage in claiming the state is awesome based on its contributions to the arts, literature, architecture, poetry etc.

However, there are some cool things about Israel, and if we put them together, we have most of the ingredients of the present Israeli political formula. The first cool thing about Israel is that it exists at all. It was a madcap project, generally greeted with incredulity and derision, that despite multiple setbacks, and the treachery of its imperial backer, achieved its goal a mere 52 years after the publication of Der Judenstaat. That’s a cool story, but we can’t expect the Palestinians to get on board with it because the state was established against their wishes and at their expense. The second cool thing about Israel is its military accomplishments. 1948 was pretty awesome, 1967 was fully awesome, Entebbe was beyond superlatives. We thought maybe that stuff was behind us and the IDF sucked now, but then there was the pager op, and taking out the whole Hizb’Allah top brass, and Iran. Nick Fuentes knows the score. ISRAEL F**K YEAH! But, again, the Palestinians can’t be expected to resonate with their own history of repeated humiliation. The third cool thing is all the hi-tech, but people don’t feel patriotic about stuff like that. The fourth cool thing Israel partakes of is Judaism. Whatever your personal beliefs, Judaism is pretty cool. It’s been around three thousand years; it gave the world monotheism; it bequeathed both Christianity and Islam, which is most of the world’s population. Props. My personal problem is that, in cannibalising Judaism, Zionism has succeeded in taking the most inane, stupid, and ugly parts of its various ethnic traditions and synthesised them into something that is worse than the sum of its parts, and then just continually tries to outdo itself in making it suck even more. We’re not going to get detained with that today, but here’s a video before we move on.

The relevant point here is that Judaism has nothing to offer Palestinians. They are not going to admire Judaism from a distance, and, even if they wanted to convert the Rabbanut won’t let them. If a Palestinian is very persistent and joins the covenant of Abraham and Moses, he can’t even be sure that an IDF soldier won’t murder him.

There is one major success story in Israel’s ability to incorporate non-Jews in the territory it controls, namely the Druze. This was facilitated by an interesting quirk of the Druze religion, which is that all of its doctrines beyond a basic stratum of ‘there is one God and you should be kind to people’ kind of stuff is kept secret by its clerisy. This allowed Israel to cooperate with the local Druze leadership to spin a tall tale about how a 12th century Shi’ite deviationist movement was actually started by Jethro, and that, therefore, Jews and Druze were best buddies from way back. The other aspect, which has become increasingly important, was that Israel has sold itself to Druze as a protector of regional minorities from the Sunni-Arab majority. The problem with applying this more generally is that this holds little attraction to Muslim Palestinians, who are the majority, or even to Christians, who have been running a century-long psy-op to convince other Arabs they are part of the majority, which ended up being a psy-op against themselves.

The point here is that you can rag on Palestinians all you want, and I’m up for it, but the inability of Zionism to incorporate the inhabitants of the territory it controls is above all a deficit in Zionism. If you don’t have any way to rule over millions of Arabs, don’t put your country on top of them. The answer of the strident Zionists is that, if there are people here it can’t incorporate, they should just be kicked out. There are a few different objections to this. First, Zionists already did that once; a second time strikes most global observers as cheating. Secondly, the new thing among the freaks is the saying that Iraq is also part of Israel, which, when combined with an insistence that expulsion is a get-out-of-jail-free card you can re-use endlessly, is objectively psychotic. Thirdly, they still can’t specify where they are even supposed to go. If this is truly the only answer Zionism has to the problem it set itself, then sooner or later Zionism will have to give way to something else. This is why I don’t criticise stuff like the Palestine Emirates Plan. People get worked up about the relatively small stuff with critiques like ‘it’s ridiculous’ or ‘it has no relationship to reality’, but at least generically it bears the features of a solution to the kind of problem we are faced with. I think behaviour of this sort on the part of Zionists should be incentivised by positive feedback. Have a tard cookie.

A postscript

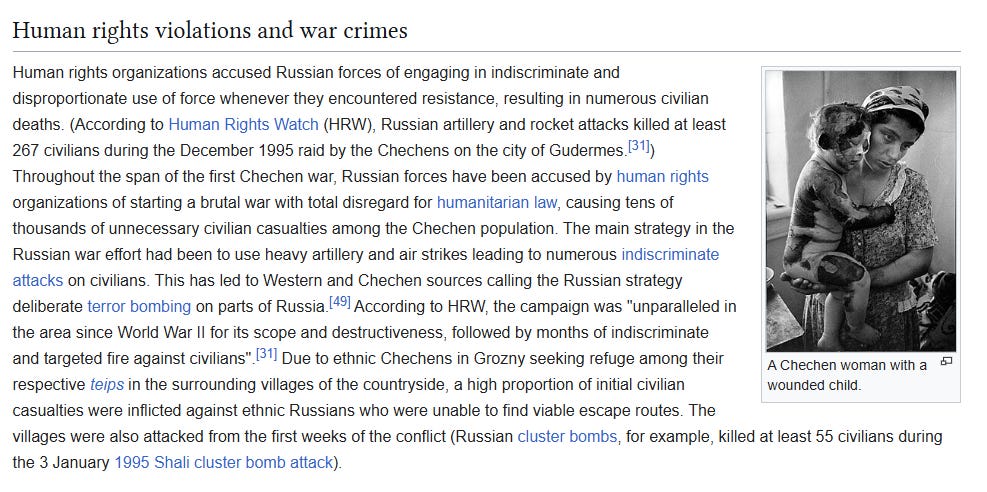

Before we sign off for the week, there’s one more thing I discovered during the Wikipedia binge that constituted my research for this article. As mentioned above, 25,000 civilians died in the Second Chechen War. That’s pretty bad, though not half as bad as Gaza (though it is worse if we go down the proportion-of-population route). More to the point, though, it wasn’t anywhere near as bad as the First Chechen War:

As you will recall, while the Second Chechen War was a triumph of Russian national might, the First Chechen War was an ignominious failure, which ended in Russian surrender, the de facto independence of Chechnya, and the rapid spread of Islamism in a formerly relatively secular population. In my based and edgy Moldbuggism, I had got the two wars mixed up in my head (I suspect I’m not alone in this) and concluded that victory was a function of willingness to kill, and kill, and kill without letting the libs get in the way. If you go through the comments section on this blog, you will find that there is no shortage of Zios eager to make the case for that today. If only we could be more cruel, more disregarding of international law, more bronze age, then we would win. If you think otherwise, it’s indicative of miscellaneous ethical and personal flaws on your part.

But it’s all bullshit. Russia tried brutalising its way to victory in Chechnya, and it didn’t work. What worked was a political strategy, which was basically a kind of ultra-souped-up version of bringing the PA in to run Gaza for us, something that our government ruled out on day one ( and not for no good reasons). A real plan might look like this, or it might look like something else, but what it will definitely involve is acknowledging the logic of ‘you win some, you lose some’, or ‘you can’t eat your cake and have it’.1 Otherwise, all the killing is for nothing, which makes it unforgivable. So don’t be surprised when people don’t forgive. It was best to just keep kicking the can.

This is the correct and original version of the phrase, and, if you queried it, you are officially gay.

Charles Napier, the British general who conquered the Sindh province in what is now Pakistan said two things that are relevant here:

"So perverse is mankind that every nationality prefers to be misgoverned by its own people than to be well ruled by another."

And

"The best way to quiet a country is a good thrashing, followed by great kindness afterwards."

The Druze also insisted on being part of the draft, which e.g. Haviv Rettig Gur has argued made a strong impression on Israeli Jews in general (and, famously, Bibi in particular). "We will put our sons in harm's way for your national project" is the sort of gesture that invites reciprocity.