The case for campus antisemitism witch-hunts

Commies GTHO

Ever since they won the midterms in 2022, Republicans have been pushing for using federal Civil Rights law to crack down on anti-Israel protests on campus that make Jewish students feel uncomfortable, and Trump has kicked this into gear. This is one of those issues that unites almost the entirety of the intelligent right-wing commentariat in opposition. It is hard to find a well-reasoned and articulate defence of the policy. Hell, it’s not easy to find a poorly-reasoned, inarticulate defence of it. Support appears to be limited principally to well-heeled (((Republican donors))) and boomers who still write letters to the editor, like, with a pen.

For my part, I made my bones over here on Substack saying that the whole concept of antisemitism which is being used to purge campuses of aggressively anti-Israel speech is meaningless pseudo theology, and the last thing Jews need right now, or at any time, is to be reinforced in our inclination to use self pity as a justification for self harm. It’s also probably not so smart for Jews being the face of what is widely perceived as an assault on free speech. Nevertheless, considered in the round, I think stringing up commie professors on trumped up charges of antisemitism is a good thing, and I hope there is a lot more of it. In truth, I already explained why I think so in that very sentence, but I can elaborate the theory behind it if you want too.

Two frozen peaches

There are two basic ways of conceiving of free speech. One is absolute, i.e. that the more speech that is allowed, the more free speech there is. At the level of a country, this is potentially something you can do, and we will leave to one side whether that is desirable or not. However, for almost any other organization, absolute free speech is clearly not desirable at all. To the contrary, it is only when certain types of speech are understood to be out of bounds that constructive speech can happen at all. Here is an illustrative video:

Examples can be multiplied without end. On Substack, there are certain people who would like to spam everyone with infinite ads for porn and Viagra, or try out endless exciting new combinations of racially charged epithets on strangers. Restricting their ability to do so is what makes the platform usable for everyone else. You can fudge the issue to a large extent with the algorithm and mute/block functions, but it is only periodic use of banning that allows for other users to effectively exercise their free speech. It is generally agreed by not insane people that Elon Musk’s substitution of a free speech regime for the capricious censorship of the old bosses made Twitter a less pleasant place for most users, and less effective forum for the debate, even for the Right.

One response to this is to conclude that the whole concept of free speech is paradoxical and can be done away with. This is not necessary, though, because there is another perfectly serviceable understanding of free-speech, namely positional. Simply put, you have more free speech the greater the proportion of people within a given organization can say what they actually want.

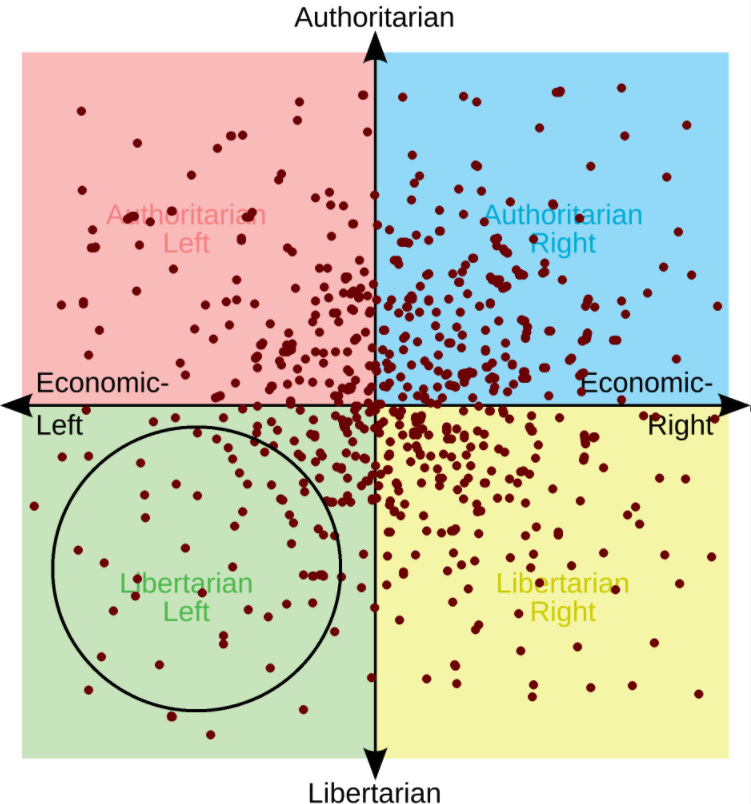

Let us explain what I mean with some pictures. Below is a political compass, with a tastefully retro scatter plot I made on Paint, representing a typical distribution of political views on society, and a black circle representing the acceptable range of opinion one can voice without consequence.

Now, one way of increasing or decreasing the amount of free speech is to make the circle bigger or smaller. What happens, though, if we keep the circle the exact same size, but move it?

Viewed from the absolute perspective, we have here the exact same amount of free speech, just in a different range. However, from the positional perspective, there has been a drastic decrease in the amount of free speech, because vastly more people are no longer able to say the things they want. This is so even if, speaking absolutely, the amount of free speech has actually increased, as in the following picture.

If we were to move from fig iii to fig i, the total amount of expressible opinions will have decreased, and a certain number of individuals as well will have lost their ability to speak freely. Nevertheless, from a positional perspective, free speech will have increased.

I think this actually approximates pretty well the way people normally think about free speech on the intuitive level, and solves the difficulties that conservatives, centrists and moderate liberals had expressing their problem with the Great Awokening. No-one actually thinks that it would be a good thing if people could walk around campus telling women they deserve to be raped, or black people that they deserve to be lynched, or the like. For the beleaguered student or professor defending his right to say that the police shouldn’t be defunded, this appeared to be an insuperable difficulty. Since they do not actually believe in absolute free speech, what right do they have to claim their speech should be protected? However, from the positional point of view, there is no problem at all. The fact that almost no-one wants to go around campus calling random people niggers is precisely the reason why there is no important violation of free speech involved in prohibiting it.

The problem with campuses during the Great Awokening was not that it suddenly became impossible to say certain things, it was that these things now included views held by a large proportion, and in many cases the vast majority, of the American population.

How the circle moves

In order the move the circle back, we have to consider how it got pushed into the bottom left quadrant in the first place. As with any sociological question, this can be answered at many different degrees of abstraction and detail, but I think the relevant one is in this video:

Here, we have the paradox of the absolutist model of free speech. Allowing crazy leftists to say what they want decreases the free speech of everyone else because what they want to do is shout at normal people, and keep shouting over and over again until normal people can’t say what they want anymore. In the absolutist model, we are stuck, but according to the positional model, there is only one problem, a practical one: how do we get this harpy off campus?

This brings us to professors who have been targeted for anti-Israel speech. Number one is Katherine Franke. Who is Katherine Franke?

In other words, a stupid b***h. Number two is Maura Finkelstein. Who is Maura Finkelstein?

Who’d a thunk it? A stupid b***h. Number three is Jairo Fúnez-Flores. Who is he?

Be gone, foul demon, to the cavern of torments from whence thou came.

What is university for?

Phillipe Lemoine wrote a long article about how antisemitism witch-hunts on campus are bad because they ‘stifle debate’. The implied model seems to be universities exist to produce truthful views about current political questions that can then be implemented in the world. If you believe that then I don’t know what to say. Maybe stop sticking crayons up your nose or something. In reality, universities are for two things:

People need a certificate saying they meet a certain threshold of intelligence, conscientiousness and conformity to get jobs that give them a decent standard of living. This is not a good thing, and there should be less of it, but for now that’s how it is.

Nerds research stuff.

As to the first, our goal should be very clear: we want normal conservative-minded people to be able to get through university without having to deal with experts in trans-colonial leprechaun furry studies haranguing them about their internalized necrophobia. It really is as simple as getting rid of as many leftists as you can, and keep getting rid of them until there aren’t any. This is a utopian ideal as yet, but every single one fired is a victory.

As to the second, it’s really the same thing. While amateur scholarship can be great and I dabble myself, what you realise, after a while, is that even the best of the internet scholars working on their own rely on those who toil in the ivory tower for much of their raw materials. In the grand scheme of things, I suppose, it’s the nerds who work on space rockets and computer science who are the important ones, but whenever I think on the topic I always come back to Geoffrey Khan. For absolute noobs who don’t know, Professor Khan wrote my favourite book, on Tiberian Hebrew pronunciation, which, because the Cambridge Asian and Middle Eastern Studies Faculty is awesome about this kind of thing, you can read for free online without even having to go to libgen, but only costs thirty five quid for a hardcover version. He’s also an expert on modern dialects of Aramaic, and is the intellectual driving force behind recent developments in historical Hebrew studies that have recently gained the attention of neo-traditionalist Jewish apologists. On top of that, he’s an awesome guy who responds generously and promptly to emails from random strangers asking him nerd questions. On the other hand, here is Geoffrey Khan talking:

Now, I’m tough, and a weirdo. At university, I quite enjoyed being accosted by disgusting filth leftists. I wasn’t there during the Great Awokening, but I wager that if I had been I’d have got through. I don’t know what Geoffrey Khan’s politics are, and I assume they are normie liberal, but the mere thought of Geoffrey Khan having to stand there, shuffling, while some human disease shouts at him incontinently about ‘equality’ overwhelms entirely my studied detachment from the world’s foolishness and replaces it with murderous rage. If you don’t think that the perpetrators of such a fecal act deserve to be tortured with knives, then scroll right on up to unsubscribe button and don’t let the door hit you on the way out.

Thinking bigger

There is only one problem with using antisemitism as a pretext to fire filth leftists from university jobs: there is not enough of it. In truth, no amount of firings would be enough to compensate for what they have done, but half a dozen nixed academics is a joke. The model should be as follows:

(i) Identify a list of misbehaving leftists at every university.

(ii) Get them fired.1

There is absolutely no reason to restrict this to antisemitism. Has [filth leftist] ever said anything positive about Mao? Tibetan students on campus feel threatened. Did he say that Stalin did some good things? Ukrainians are big right now, and they need a safe learning environment. Che Guevara? He shot homosexuals, and gay students cannot be expected to live on campus with someone who would condone that. Does this have to make sense? No, it does not have to make sense.

Some people will say that the Left will respond to such scorched earth tactics by targeting College Republicans or OUCA in return. And the downside of that is what exactly? Someone else, somewhere else, can set up the Antiversity. We are aiming here for what is, in a way, a more profound rebellion against centralizing modernity: depoliticization. A hero spoke this truth already in the long long ago, and now to us mere mortals is left the duty of honouring his memory by fulfilling his vision:

We may mention here that there was a big hoopla on the Online Right about whether it was a good thing to get some poor shop worker fired for saying something about killing Trump on social media, with the consensus being that, yes, it was a good thing. This is a pretty good example of how constrained vision leads to petty sadism.

Richard Hanania wrote similarly here: https://x.com/RichardHanania/status/1786080226344345765, noting that in practice, speech policies on campuses are more about their particular preferences than their nominal approach towards speech, in the abstract, with the corollary being that taking a harsher stance on anti-Israel speech would likely correlate with an environment more accommodating, rather than less accommodating of various types of speech more preferred by conservatives.

Unrelatedly, this article somewhat conflates the content of speech with the method of presentation.

The problem with lefties disrupting lectures or study in a library by yelling commie gobbledygook isn't just the content of their speech, but their actions that accompany that speech. And that distinction is even clearer when it comes to things like occupying campuses and attacking people.

Sure, if the goal is to ideologically purge universities of their most left-leaning elements, because they produce bad scholarship, then the distinction isn't as important. But if the goal is to allow normal conservative-minded people to be able to get through university unmolested, without having to deal with professors haranguing them about their internalized necrophobia, then that could partially be accomplished by cracking down on actions, not just speech. Who's more likely to harass normal students in or out of the classroom, some quiet leftist academic with radical views, or those who engage in or facilitate disruption? Clearly the latter. It's possible, even for lefties, to accommodate those with divergent views and to not impede them from earning their credentials and getting on with their lives.

Cracking down on disruption, rather than the content of speech doesn't even nominally run into the slippery slope problem.

Reading some comments I have the impression that many have missed the point. I don't think the author wrote it just do defend "Zionist privilege", but to put a reflection about the broad concept of "Free speech".

Based on this, I would like to post an article I read on a site I follow (it's not on substack) which talk about this issue.

Here in English :

"The freedom of individual opinion is one of the theoretical cornerstones of liberal democracy.

Everyone notices its fundamental inconsistency with practice, but few understand why this statement has gained such propagandistic importance. To understand this, we must first ask ourselves: why does a person wish to express their opinion on a certain matter? To convince others that what they are asserting is correct, or to bring about a change in society. No one who truly believes in what they are saying speaks into the void.

What does this imply? That the famous phrase, "I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it," falsely attributed to Voltaire, is a complete nonsense. A person who truly believes in what they affirm is not, logically speaking, willing to fight for someone else's opinion—because what matters to them is the affirmation of their own.

The proof of this lies in the fact that all liberal regimes have mechanisms to censor or neutralize ideas and opinions deemed uncomfortable or dangerous to the system itself. We should also remember in no chapter of European history, neither in those societies where “democratic” forms were in place, has such freedom ever truly existed.

To give a textbook example—since it is often taken as a model of modern democracy—let’s look at the essence of the classical Athenian polis. The heart of democratic Athens was the ekklesia, the assembly, whose participation was considered a duty, not a right or privilege. All adult male citizens with political rights and the capacity to bear arms took part. In other words, every citizen participating in political life received a full education, especially military, which made them fit to decide on the fate of their city.

Between the modern concept of democracy—individual “freedom,” electoral representation, political parties—and the ancient model, there is a chasm.

As for the issue of free speech, often linked to the Greek term parrhesia, the reality was quite different. No Athenian citizen was free to publicly profane the city’s gods, its ancestors, or its values. He did, however, have the right to speak freely in order to convince the members of the ekklesia to support his proposal on decisions to be made in the city’s interest. But the fact that everyone made such proposals within the framework of the laws and customs of the polis was taken for granted.

Parrhesia was not the freedom to speak nonsensically, but the faculty to criticize those in high office if one believed they were acting against the interests and values of the city.

If you read Aristophanes’ comedies—a vivid example of ancient satire—you find a kind of irony that has nothing to do with the modern one. Aristophanes mocked vices to exalt virtue. Today, instead, the regime clowns mock virtue and exalt vice.

So, if the concept of freedom of speech as it is promoted today never truly existed, and doesn’t even exist now in the way it’s presented, why is it so important for modern subversion?

Quite simply, because at first, it is used to push forward theses that a healthy and normal society would consider abhorrent. Once those ideas are accepted in the name of freedom of opinion, the underlying paradigm shifts, and it is the healthy, normal ideas that get censored—rather than the abominable ones.

The so-called Popper Paradox, which antifa obsessively repeat, is merely the final stage of this complete reversal of values, where the model becomes everything that is contrary to the norms of social life and natural law—as can be seen from the ideas being spread about abortion, drugs, LGBT issues, immigration, and everything else that could be considered rotten.

Fundamentally, liberals and Marxists are evil and perverse".