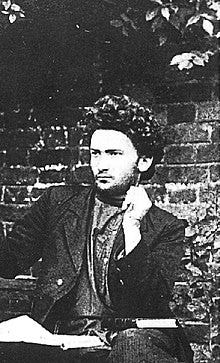

Dov Ber Borochov

'How did we get here?' part i

Note: This is the first in a series of posts introducing lesser-known Zionist figures and thinkers with some commentary of my own. Future posts in this series will be paywalled so, if you find this interesting, now is the time to cough up. Please use the comments section to make your suggestions about future subjects, though, to reiterate, unless you have a paid subscription you won’t benefit.

If you see any mistakes or questionable assertions in this post, please comment or send me a DM.

In an earlier article, I wrote about Territorialism, the more or less abortive Zionist heresy that accepted the basic premises and arguments of Herzlian Zionism, and made the logical conclusion that, given the apparently insurmountable difficulties of securing a charter to settle Palestine, another territory should be sought. The Territorialists split off from the Zionist movement following the de facto rejection of the Uganda scheme over the course of the 6th Congress, and the unambiguous affirmation of an Eretz Yisrael only policy at the 7th. During the crucial years 1903-5, when the character and destiny of Zionism as a movement was fixed, Dov Ber Borochov played as crucial a role as anyone.

Brief Biography

Dov Ber Borochov (1881-1917) started his career as an activist at age 19 when he joined the Social Democratic Labour Party, Russia’s most important Marxist party which, in 1903, would split into the two factions known as the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks. Borochov never had to pick sides in that split, however, because, in 1901, he had been kicked out of the party for his advocacy of Zionism and promotion of Jewish nationalism among workers.

Following his ejection by the future rulers of the Russian empire, Borochov played two chief roles. The first was helping to establish the Zionist-Marxist party, Poalei Tziyon (Workers of Zion), whose programme was defined by Borochov’s Our Platform, written in 1906, and whose dominant ideology was known as Borochovism. Poalei Tziyon in Russia survived until 1928 when it was dissolved by the NKVD, though many of its members had already been absorbed into the Jewish section of the Communist Party, the Yevsektsiya, the organisation tasked with converting the Jews of the Soviet Union to Communism, by hook or by crook. Poalei Tziyon in Palestine split into three factions in 1919. The leftmost part split to form the Jewish Communist Party, which was the ancestor of Hadash, today led by Ayman Odeh. The middle faction, known as Left Poalei Tziyon, who identified themselves as the faithful exponents of Borochovism, eventually became Mapam, which, in due course, became Meretz, the party of LGBTQ++++ and white supremacy. The Right Poalei Tziyon faction, led by David Ben Gurion, eventually became Mapai, and then Avodah (Labour), and led the Yishuv through the grueling War of Independence and then the fledgling state to spectacular victory in 1967, later getting massively cucked by unemployed ex-KGB agent Yasser Arafat, and going into a death spiral following the second Intifada.

Borochov’s second role was as lieutenant of Menachem Usisshkin in organizing Russian Zionism in revolt against Herzl and the direction he had led the movement since the First Zionist Congress in 1897. The background of this is as follows. Fifteen years before Herzl published Der Judenstaat, Hovovei Tziyon (Lovers of Zion) had been founded as a collection of groups promoting emigration to Palestine in response to the wave of pogroms. Hovovei Tziyon had some accomplishments, including establishing Rishon leTziyon (now Israel’s fourth largest city) and obtaining permission from the Russian government to organize formally under the auspices of the Odessa Committee. However, fundamentally, Hovovei Tziyon was a failure, unable to surmount the enormous obstacles to founding successful settlements in the malaria-ridden backwater of Ottoman Palestine, and all the energy had fizzled out of it by the end of the 1890s.

When Herzl arrived on the scene, his vision of Zionism was an overt rejection of the methods and principles of Hovovei Tziyon. Instead of sinking money into bottom-up settlement projects, Herzl’s ‘Political Zionism’ was based on the concept of obtaining a charter - from the Ottoman empire, or foreign powers who were able to bully it - encouraging and facilitating mass Jewish immigration to create a self governing polity under the light-touch sovereignty of the Ottomans. In view of their inability to compete with Herzl’s ability to raise funds, inspire the masses, or create institutions out of basically nothing, the Russian Zionists fell into line and joined his new Western-European-run movement. They were never very happy with the new arrangement, feeling (accurately enough) that Herzl was ignoring the cultural, spiritual or ethical concepts which formed the basis of their Zionism, but they, with varying degrees of reluctance, went along with him as long as he seemed to be getting somewhere.

By 1905, however, the reality was that Herzl had failed. Nearly a decade of shuttling around Europe talking with any state functionary willing to give him an audience, and repacking whatever minor scraps of attention he got in order to inspire the Zionist rank and file, had ended up with basically nothing. The Ottomans weren’t interested; if anything they were more sour on the concept of Jewish immigration than they had been when Herzl had got started. Other imperial powers had varying degrees of sympathy for Zionism as a vision - usually because they saw it as a way of getting rid of some Jews, or stemming Jewish immigration - but they weren’t going to actually do anything about it. The only success Herzl had had of any real consequence was the offer of a charter to settle Uganda, and this put the essential meaning of Zionism up for grabs. If Herzl had been correct, then the truth was that there was no logical reason to insist on Palestine when another territory was available. Palestine had initially been chosen at the site of Jewish national renewal because of cultural inertia, more or less, but the jolt of the Uganda plan was enough to break through that fog for the sober minded. Of course, there were all sorts of romantic reasons why it was Zion or bust, which really raised the question: was Zionism primarily a romantic movement?

In this debate, the natural assumption was that the Socialist wing of the Zionist movement (at that point still a minority, but one that clearly had demographic winds at its back) would take the side of territorialism. After all, it doesn’t quite shtim to advocate rational economic planning and scientific progress if you want to sink your funds into a ludicrously overpriced disease-infested swamp country when something better is on offer, just because your ancestors two thousand years ago lived there, or a religious book you don’t believe in promised that you will go back. This, indeed, was the view of Nachman Syrkin, leader of the Socialist faction at the Zionist Congress, who not only argued passionately in favour of accepting the Uganda plan, but, following its rejection, seceded from the movement to form a Territorialist organization, only rejoining the Zionist movement two years later as head of the American branch of Poalei Tziyon.

The fact that Syrkin came back with his tail between his legs to the Palestine-only Poalei Tziyon rather than leading a mas exodus of socialists from the Zionist movement was chiefly down to the efforts of Borochov, who insisted, from a position to the Left of Syrkin, that it very much was Palestine or bust, and all for very rational reasons. Under the direction of Menachem Usisshkin, Borochov worked with a broad cross-section of Russian Zionist opinion, and in particular the future leader of Revisionist Zionism, Ze’ev Jabotinsky, to achieve two goals. The first was to unify the Russian Zionists around the Palestine-only policy, and the second was to wrest control for the Russians over the Zionist movement as a whole. In both tasks, he was successful, and so here we are.

Ideology

Borochov’s writings and speeches are usually divided into 3 parts: his early writings before he had properly formed his Marxist-Zionist synthesis; true ‘Borochovism’ as exemplified by the Poalei Tziyon platform of 1906; and some speeches towards the end of his life where he appeared to retreat from this position. If, like me, Marxism is not really your thing, then you might not see the differences between these periods as being especially important.

Borochovism was supposed to achieve two things. The first was to find a space for the concept of a nation in Marxism, which meant a materialist-economic explanation for why nations exist in the same rough kind of way as classes exist, and are part of the dialectical process of history. The second was to explain why the Jewish nation specifically had to establish its own state, and why it had to do so in Palestine.

Borochov believed, in line with Marxists generally, that an inexorable historical process was dividing society into two groups: the capital-owning bourgeoisie, and the proletariat, the latter of which would in due course seize all the the capital and end class conflict for good. Prior to that, all other economic classes would be squeezed out by the forces of economic progress. The problem for the Jews was that they were concentrated in precisely the economic areas that were on history’s chopping block. Jews were tinkers, merchants, artisans, petit-bourgeois, all the groups which the coming era of mass industrial production had no need for. What this meant for the Jews was ever-escalating pauperization and persecution in an economic order that had no role for them.

In order for Jews to survive into the era of the worker’s state, they would need to become a proletariat. However, their national separateness from Russian, Polish, Hungarian etc. society - something that had been forged by economic factors long before - meant that this could not happen. In order to escape their ever-worsening circumstances, Jews had no choice but to move country, but this didn’t solve the problem, because they only found the same economic forces greeted them on arrival. Ultimately, if Jews were to survive (i.e. become proletarian), they had no choice but to go to Zion.

The obvious question, here, was why Zion and not … anywhere else? Borochov’s argument worked principally by process of elimination. Countries that had the same economic circumstances as Russia and Eastern Europe were out, obviously. More economically developed countries that already had a large proletariat ready to seize the means of production (any minute now, guys!) were even more out. That left undeveloped countries, and, out of these, Borochov argued that, by a quite remarkable series of coincidences, Palestine was the only appropriate fit. Borochov had various arguments, but the funniest goes like this:

The local population of Eretz Yisrael is nearer to the Jews in its ethnic composition than any other people, nearer even than the ‘Semitic’ peoples. It is a very reasonable assumption that the fellahin in Eretz Yisrael are the direct descendants of the remnants of the Jewish and Canaanite agricultural population, with only a very slight admixture of Arab blood; for, as is well known, the Arabs, proud conquerors, mixed very little with the people in the lands that they conquered, especially in Eretz Yisrael which was conquered as early as the time of Omar. In any event, all travellers to the country confirm that, apart from the Arabic speech, it is impossible to distinguish in any respect between a Sephardi porter and a simple labourer and fellah. And such an external similarity is important … for it is on a difference of appearance, in the absence of differences of custom and manner, that all sorts of ‘hatred’ depend. Thus the ethnic difference between the Jews of the Diaspora and the fellahin of Eretz Yisrael is no greater than the difference between the Ashkenazi and the Sephardi Jews. The local people are neither Arabs nor Turks … They assimilate willingly into any higher culture. And in the vicinity of the Jewish settlements they acquire the Hebrew culture, send their sons to Hebrew schools to learn to speak a Hebrew that is no less fluent than that of the Jewish children.1

Nailed it!

During his mature ‘Borochovist’ phase, Borochov did not support the kind of experiments in communal agriculture that would eventually develop into the kibbutz and moshav system. His view was that economic development in Jewish Palestine should take the ordinary capitalist form, which, according to Marxist theory, would inevitably produce the Jewish proletariat who would subsequently take over and establish a worker’s democracy. Borochov’s belief during this period was that Jewish settlement in Palestine was essentially an inevitable result of anonymous economic forces (what he called a ‘stychic’ process).2 As with the Marxist intelligentsia in general, the purpose of Socialist-Zionist theorists was to … well, frankly, it’s not clear to me exactly, but to relate somehow to these inevitable economic processes in a way that would make them … more inevitable?3 Schemes for agricultural settlement were a reversion to pre-scientific, ‘utopian’ socialism and, anyway, missed the point which was to make the Jews into workers, not peasants. However, towards the end of his life, Borochov seemed to figure that if Lenin could bend Marxism enough to allow him to take over the Russian empire, then he could also be a bit more flexible, too. These were the straws the Right Wing of Poalei Tziyon grabbed with both hands as they set about more or less ignoring Marxist theory altogether while becoming most active element in establishing the new Yishuv.

Observations

The first, pretty obvious, thing to say about all this is that Borochov was completely wrong about everything. The reality is that Jews who went to America were definitely not excluded by economic forces - let alone historically immutable economic forces - from participating in capitalist development and thereby forced back into the same pauperisation from which they had escaped. A significant proportion of American Jews made serious bank and joined the American elite, most of the rest became comfortably middle class. The same goes, to a more moderate extent, for the other destinations of Jewish immigration. This is just a special case of how Marxist theory - much like late antique apocalyptic texts - was really great at mapping out historical processes until literally straight after it was written.

It really can’t be emphasized enough that Zionism as an effective movement was forged by people who had birds in their head. Even if we grant Borochov a pass on being able to predict the future, why couldn’t he observe the present? Born in the Ukraine, Borochov lived in America and central Europe before moving back to Russia after the February Revolution. That was quite a lot of travelling in the pre-aeroplane days, but Borochov never even visited Palestine once. How exactly could he continue to insist that a ‘stychic’ process was inexorably leading the Jews to Zion, when he had personally been led just about anywhere else? Beats me. The most consequential decisions in modern Jewish history were made by people who were off for a loop.

Secondly, to return to the passage quoted above, though Borochov was entirely mistaken about the future course of relations between Jewish settlers and the native subsistence farmers, modern research has shown that his starting premise was correct. The Palestinians are principally the descendants of Jews who, more or less willingly, surrendered to the apparent verdict of history and became pagans, then Christians, then later (for the most part) Muslims. The Muslim portion of the Palestinian population has a substantial degree of foreign admixture accumulated, not during the Arab conquests, but the subsequent millenium and a third of being plugged into a large Muslim imperial zone. The endogamous Christians, though, preserve their Levantine Jewish genetics in a much cleaner form, cleaner than any extant group of Jews.

My experience of discussing this topic with Zionists is that they will start by insisting its not true, and then, after you have wasted half a day on it, say it doesn’t matter after all. Nevertheless, it is absolutely the case that Right-Wing Zionism is crucially premised on the idea that the Palestinians are foreigners who arrived either at the time of the Arab conquests, or, more recently according to the Joan Peters hypothesis, and should therefore basically shut their trap or get lost. In the formation of this myth, the Irguniks have been aided by arguably history’s most stupid and demented ideology, Arab nationalism, which, too, insisted that fundamentally Palestinians are not ‘from’ Palestine, either literally or in some nonsense Hegelian sense.

Naturally, it is important to demoralise Right Wing Zionists before things get out of hand and they do something really stupid, but what the positive political implications of genetic research are is less clear. Because I am not a nationalist, I do not accept the claim that a group of people ‘owns’ a particular territory just because their ancestors lived there (roughly), not least because that claim doesn’t even mean anything anyway. I’m with based Churchill on this one: ‘I do not agree that the dog in a manger has the final right to the manger even though he may have lain there for a very long time’. In truth, finding out that Palestinians are the descendants of 2nd-temple Jews allowed me to see things from the Roman perspective a bit better, but mostly it convinced me that Rabban Yohanan Ben Zakai was right to throw in the towel and start over. Sometimes, your moral loyalties just need to leapfrog. More than that, I don’t know, but it certainly does seem to change the way one feels about expulsion.

Please share any observations or queries about Borochov in the comments, but more importantly

This is taken from D. Vital, Zionism: The Formative Years, p. 406. There is a collection of Borochov’s essays translated to English, but it does not include the relevant one:לשאלת ציון וטריטוריה, and I have only been able to find snippets in English and Hebrew.

His platform for Poalei Tziyon states that ‘Our Palestinism is neither theoretical nor practical, but rather predictive.’‘

Borochov writes ‘Utopianism always suffers because it strives to ignore historical process. Utopianism wishes by means of human endeavor to create something not inherent in social life. Fatalism, on the other hand, assumes that the effective participation of human will is impossible with regard to these historical processes, and thus it drifts passively with the stream. Utopianism knows of no historical processes. The Utopianists fear to mention the phrase "historical processes"; for they see in the so-called historical process fatalism and passivity. The fatalists, on the other hand, fear the conscious interference with the historical process as a dangerous artificiality. The fatalists forget that history is made by men who follow definite and conscious aims and purposes only when those aims and purposes are well adapted to the historical necessities of social life.

We ask, "What role can our will, our consciousness, play in the historical processes of Jewish life?" To the conscious interference of human will there must be added another factor, that of organization. Organization is not a mere sum of individual efforts, but rather a collective social force. Along with the historical social tendencies we must introduce planning. To regulate historical processes means to facilitate and accelerate their progress, to conserve social energy, and to obtain the optimum results from the labor put forth.’

A weak reading of this might be that you can change history through organisation, but only if what you are trying to achieve fits with broader trends, but I think it is intended to be read more strongly than that, though I don’t know exactly how.

In the spirit of 'vote early, vote often' and having just finished Oren Kessler's Palestine 1936 (which seemed to me to be very good), I'd be interested to learn more about Moshe Shertok.

I'd like to know more about the doomsayer tradition in late 19th / early 20th c. Jewish thought, especially the people who saw it really early like Moses Hess because I always got the impression that at some point the early callers were lucky guessers more than they were correct.