Modern Jewish History part i

The horror

There is a thing I do, which is comment on other people’s articles and point out why they are wrong and also suck. I’m good at it too. I wouldn’t say I enjoy it exactly. Maybe I did once, it’s hard to remember, but now it’s kind of a grim compulsion. I’m not proud of this behaviour. It’s condemnable, maybe even contemptible, but I’m not going to stop, so I thought I might as well get paid for it. That’s what this Substack is: when I write a comment that’s more than a few paragraphs, and I remember before hitting send, I turn it into an article instead. If the conclusion is not as good as it sounded in my head, or it’s good but it’s too spicy for general consumption, I stick in a paywall. Free money.

However, when I started this blog, I did have kind of a theme I was going for. The idea was the Clear Pill on modern Jewish history. I honestly don’t know what is going down with Boldmug nowadays, but he was once a genius. I promise. Life-changing stuff. Not life changing in the sense that your life changes, but that you see it in a new way. Much worse, but also kind of better. But then sometime after October 7th I realised it was all fake. I hadn’t been seeing life differently at all, I’d just been pretending. Believing Democracy is fake: that’s easy. I’d even managed to convince myself that I thought Zionism was fake, but this was transparent self-deception. ‘The evil Zionists won’t let us kick out all the Arabs and build our Torah State!’ Very cool משכיל בינה, you idiot. But then I really did it and I just didn’t believe in anything anymore. As the master said:

What you realize as a nonidealist is that it’s okay not to participate in these rites. You don’t even need to deny them. You don’t need to raise your hand and say “I hate the environment,” or “I think I might be a racist.” You can practice what Czeslaw Milosz called ketman, not only rejecting the whole ridiculous circus, but deriving real visceral pleasure from the exercise of pretending to conform with it.

And instead, you can love only the things that you yourself love, pity only the people that you yourself pity, and feel guilty only for any crimes that you yourself have committed.

In fact, you should cherish the fact that you live in a society which indulges itself in absurd political parodies of these emotions. Because when you actually feel the real things, and distinguish them from their sentimental counterfeits, you get to feel special. And everyone likes to feel special—not just young people.

Did I feel special? I’m not sure. I recall feeling very cold, almost dead, but that’s because this house doesn’t have radiators. I feel cold right now. Nevertheless, I thought I would share this cold with the world, and it was going pretty dandy. Literal gentiles were sending me messages suggesting podcasts. Scott Alexander shared my stuff and then banned me, and shared me again. Blog was cooking.

It all started falling apart when I wrote the article about disgusting pig Ben Gvir visiting 770 and endorsing on video their chair-worship cult. I knew it was stupid, but I had to do it anyway. The whole article took maybe 40 minutes of manic typing. I was just so disgusting. I’m exactly as disgusted now as I was when I wrote it. It’s very obvious that all of the ‘religious’ members of the government would leave immediately if they weren’t total phoneys, and I am repulsed by anyone who would vote for these parties. And that’s how, when you thought you were out, you pull yourself back in. The truth is I’m just an extreme guy with a lot of extreme opinions. As they say, the only person you can change is yourself, but you can’t do that either. So sucks to be you. Unless you’re a well-adjusted person with good social skills, which must be nice.

Anyhow, while the blog concept fell through, the blog goal is going OK. Could be better, but OK. But I caught myself wasting time again recently debating extremist takes on Jewish history for free, and I committed to making a post about it. This is far too big for one post, though. Likely far too big for ten. What I’m going to do is keep typing until the tab at the top saying ‘too long for email’ pops up and then call it a day for a week. Some of the things I’m going to write I’ve read a lot about, some of them a bit, some of them I’m just going to wing it. If you have corrections, throw them in the comments section. If you don’t, maybe read a book once in a while. Let’s go!

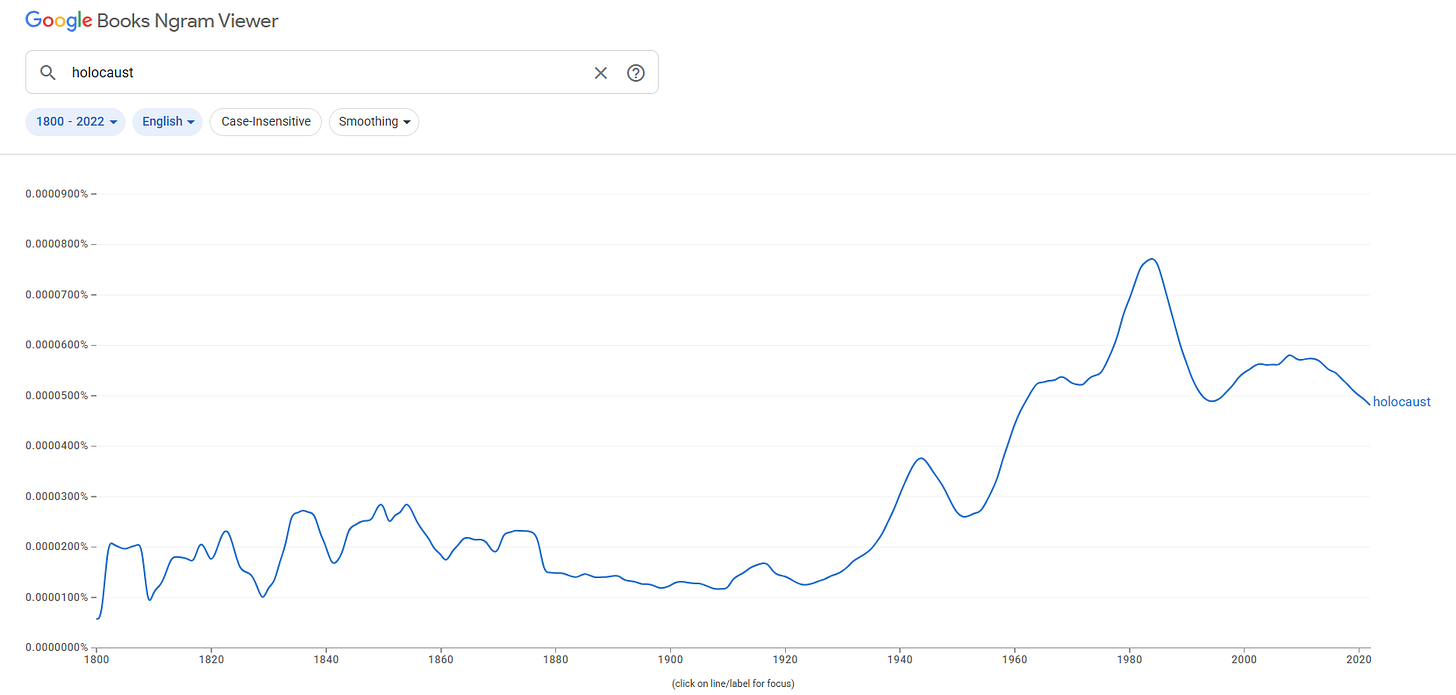

The central fact of modern Jewish history is the Holocaust. Everything else is insignificant except in so much as it finds significance in relation to it. I have tried, with distinctly limited success, to explain to our fellow Jews that this is not the same as the Holocaust being central to modern history simpliciter. That is clearly not the case. It was a marginal event in the course of WW2, which most people involved didn’t know was happening, or think especially important if they did. The whole rancid history of the mid-century collapse of human civilization would have played out almost exactly the same if the SS had managed to keep it in their pants. Certainly, there have been innumerable subsequent knock-on effects. The Holocaust was an act of concentrated dysgenics of the sort the liberal welfare state can only gesture at; without it, we would perhaps have not got stuck so long in the impasse of string theory. Maybe there would be moon bases. But by these standards we can also argue ourselves, if we only try hard enough, into thinking that a butterfly’s fart was the most consequential event in history too.

The importance of the Holocaust to global affairs came afterwards, when, amidst the grim wreckage of the original dopey plan to divvy up the world in a progressive alliance with the Soviet Union, the United States needed a justification for why it had conquered the world. In other words, the significance of the Holocaust to world affairs is not as fact, but as myth. Exceptionally stupid people take that sentence to mean that the Holocaust didn’t happen. Exceptionally stupid people say a lot of things; best to try and ignore them.

However, for Jews, the Holocaust just obviously is the most important thing that happened since the calamity of 66-136 CE. When Theodore Adorno said there can be no art after the Holocaust he was indulging in group narcissism, but if he had said there can be no Jewish art after the Holocaust, it would have been perfectly reasonable (and also, to be quite blunt, explain quite a lot of things in a more charitable light than seems possible otherwise). Looking backwards as a Jew is to stare into a void of cattle trucks, and exhaust pipes, and piles of stinking flesh, behind which lies only a pointless blur. To put it less portentously, if modern Jewish history ends in such total, numbing failure, it must be, both essentially and in its details too, a story of failure. All its heroes are failures; if they hadn’t failed, then it wouldn’t have ended as it did. Either their influence was limited, or their influence was wrong, or, like King Josiah, it was all too late anyway; there are no other options.

The only way out of this is to see the Holocaust as something orthogonal, something that comes from outside, like a speeding train that takes out a family minding their own business, at a stroke wiping out all their dreams, hopes, fears and regrets, but not in such a way that it changes the meaning of the story till that point. If so, you can look at Jewish history as a narrative with its own internal plot and subplots that was cut short at random when viewed from the perspective of its own internal logic. Such a perspective is not ridiculous at all; quite a good case can be made for it. But it is an atheist case, and I am not an atheist. Therefore, if you don’t read everything that follows with a sense of growing doom, bulging until it is ready to crush everything, then I have failed to get my point across.

Everyone knows that history repeats itself, first time as tragedy, the second time as farce. Banger line, no doubt, but, actually, it’s just a description of one historical event, and arguably not a great one either. Modern Jewish history ends as tragedy and starts as farce. Just as the tragedy was total, inescapable, all-encompassing, so was the farce. If you forced me to pick, it’s hard to say whether the farce was more farcical or the tragedy more tragic. We are talking, of course, about the messiahship of Shabtai Tzvi declared by his prophet, Nathan of Gaza, in 1665.

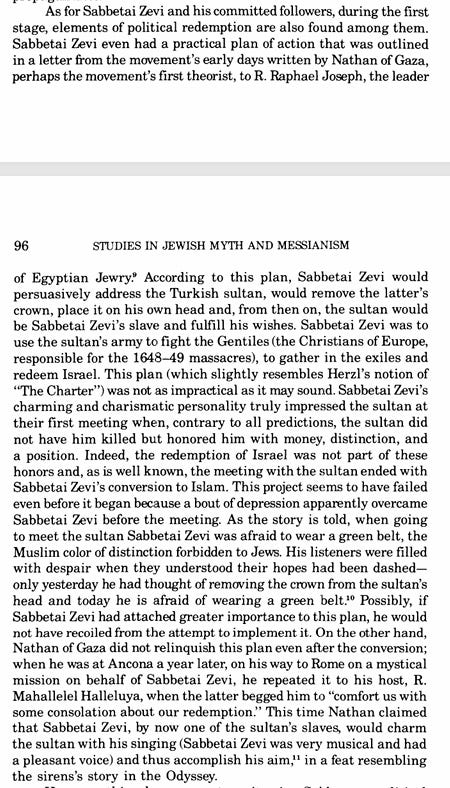

Shabtai Tzvi had precisely none of the qualities that one is entitled to demand of a messiah, but, more than that, he had none of the qualities you would demand of the junior manager of a Burger King. He was a drifter, sponging off his brothers to pursue scholarship without having much to show for it, and prone to extended spells of melancholy. Even before his conversion to Islam, he was known for weird acts of antinomianism, including saying a special blessing on consuming forbidden foods, or celebrating the whole annual calendar of festivals in a week for no discernible reason. He would tell his followers that he could fly, but they weren’t worthy to see it.1 He was married three times, but each time he refused to consummate. Strictly speaking, he was married four times, because he also had some kind of cringefest marriage ceremony with a Sefer Torah. His plan for redeeming the world was to rock up at the Sultan’s palace, say psalms and wait for cosmic forces to start kicking off.2 In other words, he was a massive weirdo. It would be bad enough if he was accepted as messiah by the bulk of the Jewish people in spite of being a weirdo, but it seems more correct to say, as we shall see, that being a weirdo was actually his specific qualification for the job.

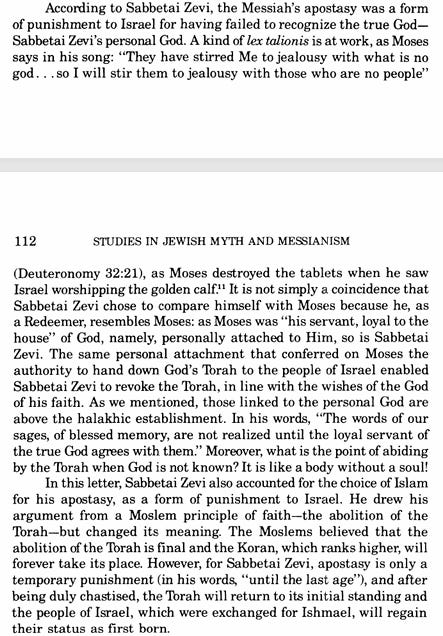

After Shabtai Tzvi committed apostasy, most Jews moved on to something else. That’s not a mystery. The mysteries, at first sight, are why (a) a majority, perhaps a very large majority, of Jews got caught up in the initial ecstatic enthusiasm over this total bozo and (b) a significant minority, probably around 5%, and a greater proportion of the religiously motivated, continued to believe in him even afterwards, and for a good century and a half until it really petered out. If you get crucified and you manage to go out declaring אלי אלי למה עזבתני like a boss then, honestly, that’s pretty based and you kind of deserve to have some kind of posthumous cope movement keeping your messiah flame alive. Shabtai Tzvi, by contrast, ended his campaign of global redemption in the absolute gayest way imaginable. Converting to Islam is forgivable given that the alternative was probably getting flayed alive, but he couldn’t even be a pussy like a man. Instead, he sent out messages to his followers saying that he was still messiah, and his conversion was all part of his special mission. Nathan took this as his cue to develop an extended version of Lurianism in which the sparks most deeply trapped in the peels3 can only be released by calculated acts of deviancy on the part of the great soul of the messiah, an idea which in due course would become the generator of radical Sabbatian thought and practice. However, Shabtai Tzvi actually never justified his apostacy this way, instead, he had a simpler idea, actually two of them:

The answer to our two conundrums, which represents the central generative crux of all that follows, is that, as well as being a clownishly shambolic fiasco, the good news of Shabtai Tzvi’s mystic kingship was also the culmination of a great movement that had developed over the past 200 years, and had rapidly spiralled out of control over the last thirty of them. You already know what I’m talking about, of course, but you’re going to have to wait because the pop-up just popped up.

No, really, this is actually real.

Usually, this is transliterated as kelipot, instead of translated as the word ניצוצות is, probably because it sounds very lame to liberate a spark from a peel.

“Looking backwards as a Jew is to stare into a void of cattle trucks, and exhaust pipes, and piles of stinking flesh, behind which lies only a pointless blur. To put it less portentously, if modern Jewish history ends in such total, numbing failure, it must be, both essentially and in its details too, a story of failure. All its heroes are failures; if they hadn’t failed, then it wouldn’t have ended as it did.”

I really don’t get this. Is Mendelssohn really a failure? Is there not a treasure trove of pre-Holocaust European Jewish art, philosophy, science that is still around? I don’t really understand the bullet train analogy. We can see the Holocaust as something that coherently fits in with the narrative of European Jewish history, but still not view everything that came before as a failure.

Also, why is the Holocaust a good excuse for the US “taking over the world?” Why couldn’t the soviets make the same excuse, given they liberated the camps too? There are other explanations for the chart you showed, such as, off the top of my head, more information being revealed abt holocaust, trauma wearing off enough for survivors to talk about it more, children of survivors being more willing to speak about it than survivors themselves, etc.